Chapter 1: Cultural Relevance

Creatine has been quietly delivering superlative energy in high school locker rooms and GNC stores for over 30 years, but in the past five, creatine sales have increased by 300%[1]. Why has everyone suddenly discovered it now? If you felt bombarded by ubiquitous sales pitches from influencers and periodicals, you're not imagining it. Business Insider, Women's Health, and (not to be outdone) Nature are all rushing to tell you (and your cellular metabolism) what's very old news: creatine supplementation is all upside and going to deliver in every energy-intensive situation it's invited to (so long as the fundamentals are structurally sound; more on this later).

The biological apparatus for creatine's success was already there. Creatine works, and the research proving it has been piling up for decades. But something shifted. What was once dismissed as "bro-science" is now being championed as the wellness world's most underrated supplement. The difference? We're finally paying attention to what actually happens at the cellular level when you need that extra push, whether it's a final rep, a mental sprint, or any moment of peak demand.

Chapter 2: Required Reading

Yet, skepticism is always warranted prior to initiating any new intervention, whether it's an over-the-counter supplement or a brand-new injectable weight loss drug. You're probably asking yourself, how could one relatively simple chemical compound, in such marginal doses, safely impact everything from attention span to bench press PRs? That seems too good to be true.

It does sound too good to be true. But indulge in a thought experiment. If we wanted to target broad improvements in performance with a theoretical drug, a pretty good target would be something that improved energy utilization. (For you nerds out there, this would be called an ergogenic aid). Our theoretical molecule would need to increase energy production in an on-demand fashion while not causing any untoward issues lingering around while waiting for us to work out. Finally, it would be nontoxic, preferably something our body recognizes and has millions of years of evolutionary familiarity with. As it just so happens, creatine fits the bill for these principles perfectly. But to understand why, it's important to have a basic understanding of how our cells (and hence ourselves) make and utilize energy.

Chapter 3: Energy

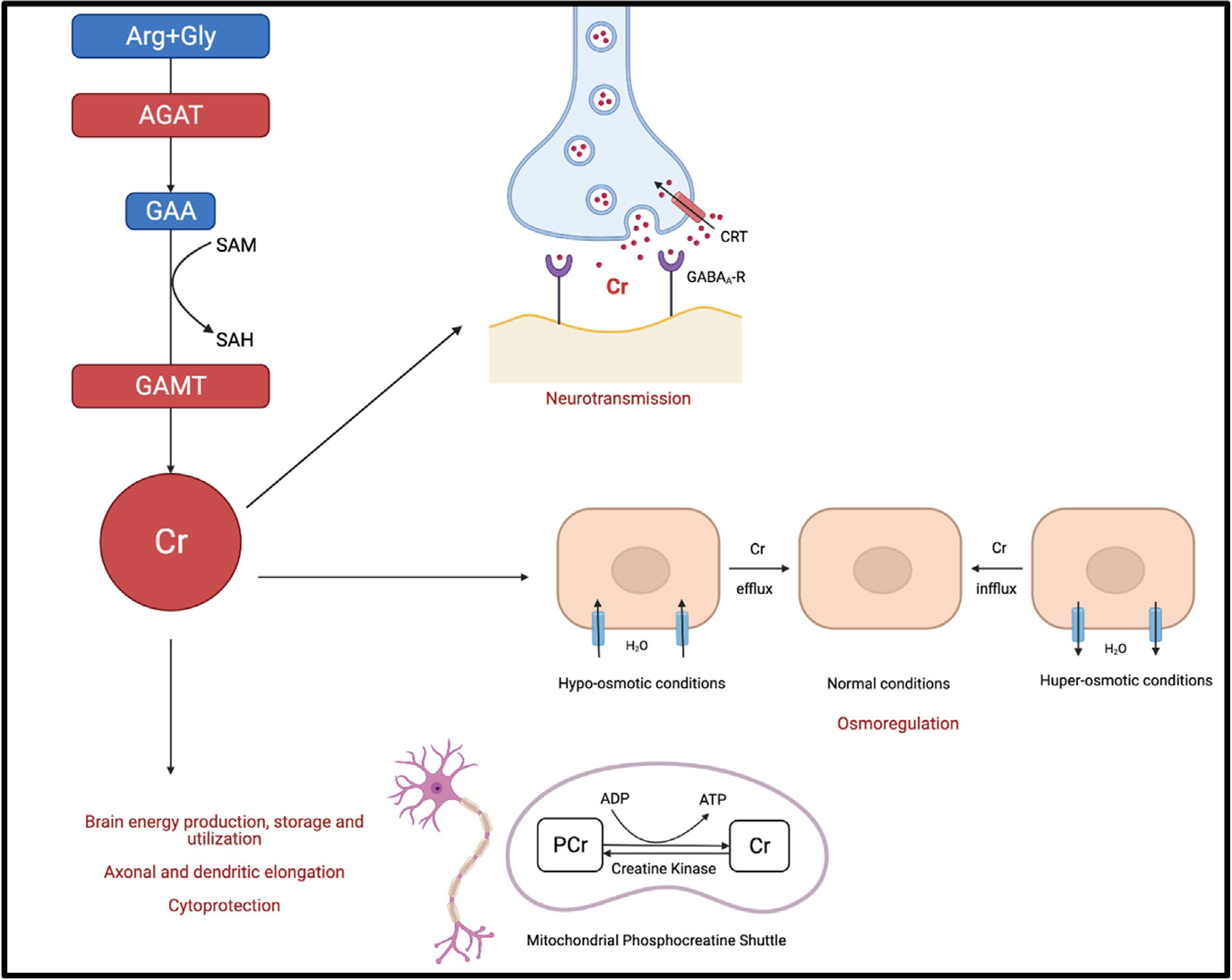

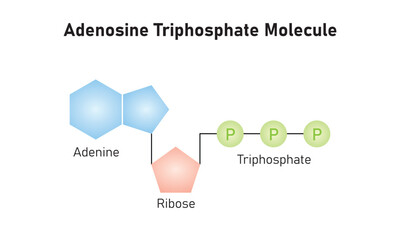

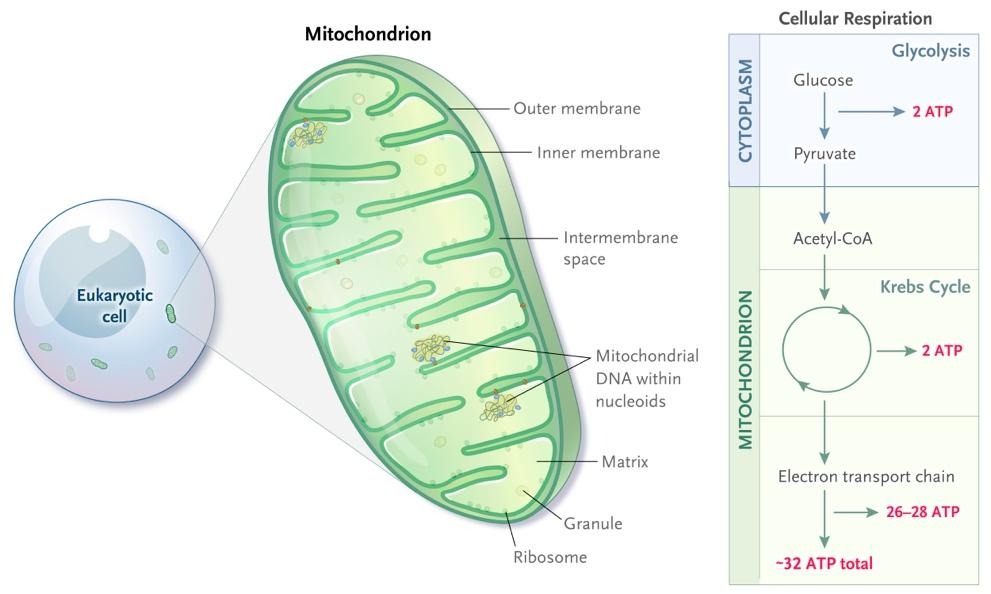

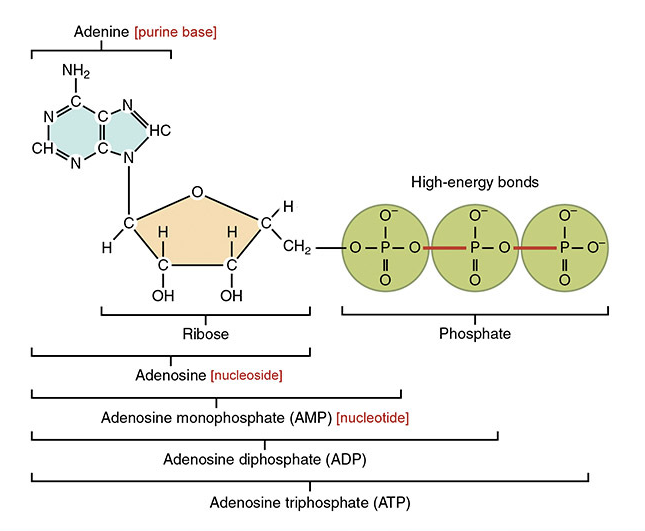

At the cellular level, the currency of energy is adenine triphosphate (ATP)[2]. In multicellular organisms like us humans, the principal mechanism of ATP production is via aerobic respiration, utilizing the molecular combustibility of oxygen we breathe in to drive ATP generation in our cells, with carbon dioxide as the exhaust we exhale.

The location of aerobic respiration is in the engine, or powerhouse of the cell, the mitochondria (Figure 2), where glucose or fats are metabolized through a series of chemical reactions, generating 32 ATP from the metabolism of a single molecule of glucose.

A critical issue immediately arises with ATP as a source of energy. ATP isn't very stable. It's good on-demand energy but quickly degrades, losing a phosphate group, and degenerating into adenine diphosphate (ADP), a much more stable, but much less available energy source[4]. If only there was a molecule that could quickly replenish the missing phosphate group...

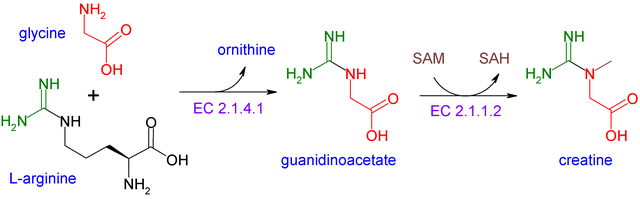

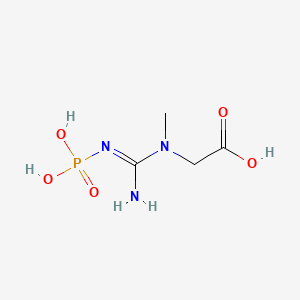

Creatine [N-(aminoiminomethyl)-N-methylglycine], exists in two forms: an amine and an imino form, something in biochemistry called a "tautomer". This is a handy characteristic insofar as it allows creatine to easily be converted to phosphocreatine (via creatine kinase; more on this later), thereby creating a reservoir (or battery) of phosphate. With this extra phosphate, it can supercharge lackluster ADP back into ATP. Simply put, the more phosphocreatine available, the more energy is immediately regeneratable.

.png)

Like a battery, phosphocreatine can be used temporally to boost energy (i.e. squeezing one last rep out of skeletal muscle by delaying fatigue, and thus facilitating more hypertrophy) or spatially, regenerating ATP at specific muscle (myofibril) sites of highest demand for a given activity. In the aggregate, these changes allow for more intense training and over time, more adaptive changes.

Chapter 4: A Brief History of the Science of Creatine: 1832-1996

To truly understand how powerful and fundamental creatine is to our biology, it's worth tracing the history of this impressive molecule. The story of our collective awareness of creatine, from its discovery in 1832 to its global cultural capture via social media in the past decade are fascinating unto themselves, but more importantly, informative to the underpinnings of why this molecule deserves the hype.

The primordial character history of creatine is the Frenchman Michel Chevruel (Figure 2), who first discovered it in 1832 (or 1835). He derived the name from the Greek kreas meaning "meat". This was because Chevruel was basically boiling meat and evaporating the solution attempting to isolate and identify organic compounds[7][8]. In a particular solution, he identified a distinct crystalline structure. He knew it contained nitrogen, was present in high concentrations in muscle tissue, was soluble in water, but not much else. Other than it tasted bitter -- taste was the mass spectrometer of the 1800s.[9]

His work was followed by Justus von Liebig. Liebig was able to reproduce Chevreul's findings and made important new discoveries. He found that creatine wasn't scattered randomly through the body, but concentrated in muscle tissue. From that, he correctly inferred that creatine was no mere bystander but a constituent of muscle function itself. He went further: creatine doesn't stay static. It transforms into creatinine, which is then cleared in the urine.

That simple observation was revolutionary. It showed that chemical transformations underpin physiology — that a molecule could move from a functional role in muscle to a measurable waste product in urine. Liebig intuited what we now take for granted: biochemistry leaves footprints that can be measured.

Creatinine is one of those footprints. Today it's a cornerstone of clinical medicine: a basic metabolic panel staple, used both as a rough gauge of muscle mass and as a surrogate marker of kidney function. What Liebig saw as a chemical curiosity has become a number every clinician reads daily and one of the most familiar molecules in medicine.

After Chevruel and Liebig, the world would have to wait another 50 years for another breakthrough to come. In 1927, Cyrus Hartwell Fiske and Yellapragada Subbarow of Harvard Medical School solved the next part of the creatine puzzle in a brilliant way. Prevoiusly, they had pioneered a method of determining the amount of phosphate in am organic sample by exploiting a particular reaction of phosphate with other chemicals, ultimately producing an intense blue color proportional with the amount of phosphate present in the sample. While utilizing this tool on skeletal muscle, they identified a previously unknown compound: Phosphocreatine. Fiske and Subbarow went on to show that phosphocreatine levels dropped during muscle contraction, while inorganic phosphate increased. The was a critical insight. It suggested that phosphate and creatine were extrinsically linked to muscle contraction. And it raised a big question: how? Although Subbarow and Fiske were unable to solve that mystery they continued to used of their ingenious phosphate-dectection system to great success, becoming two of three co-discovers of ATP, in 1929.

In the 1930s, numerous scientists, principally David Nachmanssohn (of Germany) and Einar Lungsgaard (of Denmark) solved this mystery by examining muscles in contraction and relaxation. Through independent experimentation, the two of them found

- contracting fast twitching muscles contained more phosphocreatine than slow switch muscles

- muscle could contract with the presence of phosphocreatine alone

- Where as phosphocreatine rapidly broke down during the first few seconds of muscular work, ATP levels remained unchanged, despite the energy demands of contraction.

Integrating these observations together, they hypothesized what we know to be true: phosphocreatine was nobly sacrificing is phosphate to keep ATP levels stable. This idea became known as the phosphagen system: phosphocreatine buffers ATP by donating a phosphate to ADP[11].

This brings us to the first important enzyme in our story. Creatine kinase.

Intermission: Enzymes

Up to now we've been talking about molecules: creatine, phosphocreatine, ATP, ADP. But we should pause to appreciate the enzymes that make all of this chemistry possible, particularly creatine kinase.

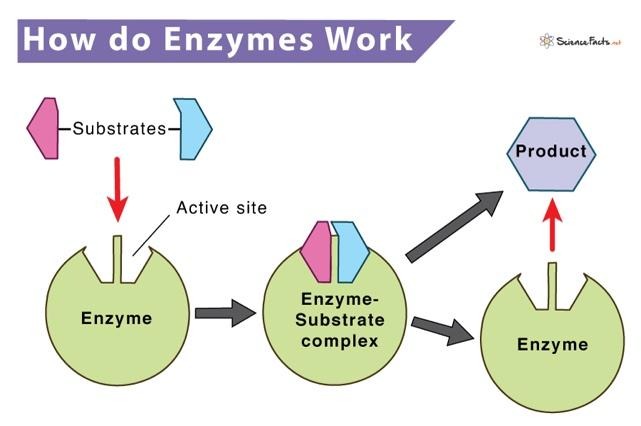

If high school biology is a hazy memory in your rearview mirror, don't despair! Enzymes are special types of protein that speed up chemical reactions in living things. Without enzymes, most reactions in your body would be too slow to keep you alive. They act likely tiny biological machines and arranged molecular marriage practitioners, grabbing onto molecules, helping (or forcing) them to react. Enzymes have unique shapes, and a particular area called an "active site"; this fits certain molecules (called substrate) like a lock and key. Once the substrate binds, the enzyme stabilizes the reaction, driving down the costs, and making the reaction happen millions of times faster than it would on its own. Enzymes are specific to dedicated chemical reactions, are reusable, and are typically very tailored to unique environments they work in (temperature, pH etc).[12]

So now you know what enzymes are and do. But's what's a kinase? A kinase is a particular type of enzyme that adds a phosphate group to a substrate. In biology, protein with the suffix "kinase" after it, means it's just adding a phosphate group to something. And now that you're both an enzyme expert and a creatine expert, you can see why creatine kinase (CK) was the next piece of the puzzle for scientists to understand how creatine worked it's metabolic magic.

Discovered in 1934, by 1929 noble prize of medicine winner Otto Fritz Meyerhof, creatine kinase cemented the understanding of phosphate metabolism in skeletal muscle. If we consider creatine the battery we use to draw energy on demand, creatine kinase is the charger for the battery. Ironically, it takes ATP to drive this enzymatic reaction. But as we already know, it's better to sacrifice the short-lived ATP for phosphocreatine (a much more stable energy reservoir) then for ATP to spontaneously break down into ADP with nothing to show for it.

Throughout the 1940s-1960s scientists continued to identify more specific enzymes, they found three particularly important kinds (isoenzymes) of creatine kinases. The first was mitochondrial CK. As its name implies, it was found in the mitochondria and loads creatine with phosphate generated from aerobic respiration via oxidative phosphorylation.

Next, they discovered a non-mitochondria creatinine kinase -- cytosolic CK (the cytosol is aqueous solution within cells). Cytosolic CK functioned to regenerate ATP right at the sites of muscle contraction (myofibrils) and other ATP-demanding sites and to deliver them, like the world's Tiniest Door dasher, to wherever they were needed at the moment.

Just like Pedro Pascal can pull off flamboyant androgenous roles one year then transition into the Platonic ideal of grizzled Texas (somewhat fragile) masculinity another, creatine kinases powerfully add multidimensionality to the effects of creatine on our body. Cytosolic CK be further broken down into subclasses. Each of these are built of two "subunits", named M (for muscle) and B (for Brain), based on where they are predominantly found. For Cytosolic CK, there are three main types.

- CK – MM: Main isoenzyme in skeletal muscle (and will go through the roof if you were to measure your blood levels after a HIIT-workout)

- CK – MB: Predominantly found in cardiac muscle, and (prior to the advent of troponin, was a biomarker that was measured to access for heart attack)

- CK – BB: Found in the brain and smooth muscle

Mitochondrial CK Isoenzymes are made of four subunits, and located, as their name suggests, immediately adjacent to mitochondria. There are two main types:

- ubiquitous mitochondrial CK – found all around the body, particularly in brain and smooth muscle

- sarcomeric mitochrondrial CK – found mainly in the heart and skeletal muscle system, and specifically work to maintain high-energy phosphate transfer in contraction.

Ultimately, these enzymatic discoveries, and the integration of their function, revealed how creatine was able to meet the needs of energy activation but shuttling phosphate quickly and efficiently around they body.

As you may have noticed from the figure above, creatine kinases where everywhere, and scientists quickly discovered that creatine is used throughout the body, especially in tissues with high energy demands. The finding that creatine kinases are abundant in the brain highlighted that this "battery system" is not only about squeezing out another bicep curl but may also play a role in boosting cognitive performance (more on this later). It also hinted that creatine was not just an energy transfer system, but was itself a potential regulator of other bodily functions or homeostasis.

While using CK as biomarkers was used in medicine, it took until the 1970s-1980s for exercise scientists to look at creatine entirely through a "performance" lens. In landmark studies by Swedish physiologists Hultman & Sjöholm, they performed muscle biopsies of the quadriceps, and found that for nearly the first 6 seconds, ATP stayed nearly stable while phosphocreatine dramatically dropped off. This proved that in the initial few moments of muscle contraction, nearly all energy utilization with achieved from regeneration of ATP from phosphocreatine, with other energy productions engaged thereafter.

Unequivocally established as important, the idea of supplementation of creatine was not seriously studied or adopted until the 1990s. Hultman, and others performed the first published oral supplementation of creatine in 1992. It interspersed creatine supplementation vs. placebo (cross over study) in 12 participants (9 men, 3 women) who were tasked with doing 30 maximal isometric contractions (lateral knee extensions if you're interested) interspersed with 1 minute recovery periods. The participants performed this protocol once, and then were either put on 5g of creatine/day or placebo. The authors found muscle torque production was improved in the creatine group with respect to force generated across the protocol, particularly in the last 10 contractions. This small study had much less impact on popular imagination then did the revelation that several accomplished athletes in the 1996 Olympic Games were supplementing with creatine.

An excellent tale of this is captured here for those interested (The Untold Story Behind Creatine)

Also in 1996, Volek et. al found a critical end point that no gym bro could reasonably pass up: the moment you've been waiting for: proof that your bench press improves on creatine. In this double-blind study, researchers asked whether a week of creatine loading could give trained weightlifters an edge. Fourteen men performed repeated bench press (5-sets) and jump squats (at 30% of their one rep max), before and after supplementation. The results were impressive: creatine users (25 grams of creatine a day, spaced out across 4 doses) squeezed out more reps on the bench and generated higher power in every squat set. Their post-workout lactate was higher too; not from inefficiency, but from pushing harder. On top of that, they gained about 1.4 kg in just a week, like a combination from water or lean mass.[14]

By 2000, creatine supplementation was ubiquitous in fast-twitch muscle sports. Its critical role in the first few moments of muscle activation were thoroughly understood. But the next 25 years of science suggested creatine instrumental in our physiology far beyond our musculature. Before we conclude, below is provided an excellent pictoral representation of the 170 years of science discovery we just reviewed.